- Home

- Lee Martin

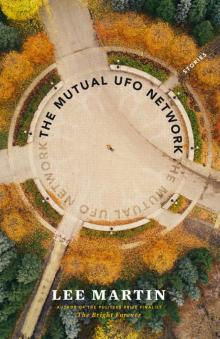

The Mutual UFO Network

The Mutual UFO Network Read online

THE MUTUAL

UFO NETWORK

THE MUTUAL

UFO NETWORK

STORIES

LEE MARTIN

5220 Dexter Ann Arbor Rd.

Ann Arbor, MI 48103

www.dzancbooks.org

THE MUTUAL UFO NETWORK. Copyright © 2018, text by Lee Martin. All rights reserved, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Dzanc Books, 5220 Dexter Ann Arbor Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48103.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Martin, Lee, 1955- author.

Title: The mutual UFO network / Lee Martin.

Description: Ann Arbor, MI : Dzanc Books, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017044833 | ISBN 9781945814495 | eISBN 9781945814686

Classification: LCC PS3563.A724927 A6 2017 | DDC 813/.54--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017044833

First Edition: June 2018

Cover design by The Frontispiece

Interior design by Leslie Vedder

This is a work of fiction. Characters and names appearing in this work are a product of the author’s imagination, and any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

THE MUTUAL UFO NETWORK

ACROSS THE STREET

LOVE FIELD

THE LAST CIVILIZED HOUSE

BELLY TALK

BAD FAMILY

WHITE DWARFS

REAL TIME

DRUNK GIRL IN STILETTOS

A MAN LOOKING FOR TROUBLE

THE DEAD IN PARADISE

DUMMIES, SHAKERS, BARKERS, WANDERERS

For Cathy

THE MUTUAL UFO NETWORK

THE LAST TIME I SAW MY FATHER, HE WAS IN OUR GARDEN TYING PEA vines to bamboo stakes. The vines, he told me, needed something to latch onto, something to climb; otherwise, they would snake along the ground and tangle and make a mess, and the one thing he didn’t need, then, was a mess. “You know what I’m saying, don’t you, Nate?”

“Right,” I said. “Keeping things in line.”

“Check.” He winked at me. “All our ducks in a row.”

It was October. The scorching heat of summer had eased, and the fall rains had come. Each morning, we woke to drizzle, to the sound of water dripping from the eaves. The leaves on the red oaks were turning brown, as was the grass, everything fading to that camel’s dun that was Texas in autumn, only an occasional burst of red from a Bradford pear or a spritz of green from my father’s fall planting to give the world any color at all.

The pea vines would have another month before the first frost. “You’ll be back before then,” my father said, “and we’ll put everything down for the winter.”

I was going to visit my mother in Virginia, where she’d moved when she and my father separated. I was going because I couldn’t bear to be with him even though, in the spring, I’d made the decision to stay.

“You don’t have to love him,” my mother had told me. “There’s no law.”

But the truth was I did love him—at least, that’s what I called the ache that stuck in my throat every time I saw him, when he thought he was alone, tip his head and cover his face with his hands. Or each morning when I came into the kitchen and saw a place set for me at the breakfast table. A cereal bowl and juice glass and coffee cup, all turned upside down to keep out the dust. A cloth napkin rolled and held with a wooden ring. Most mornings, there would be a note held down with a spoon. APPLES IN THE FRIDGE, it might say in my father’s small, labored handwriting. PAPER SAYS RAIN. DON’T GET CAUGHT IN THE WET.

Sometimes I stood at the window, hidden by the thick folds of the drapes, and watched him on the lawn, picking stray bits of cypress mulch from the grass or the carpet juniper that ran along our front walk. He got down on his hands and knees and crawled, plucking up any shaving or scrap that had washed out from our flowerbeds. Then he got to his feet and stood there, hands on his hips, surveying the lawn until he saw something he’d missed. Often, he kept at it until dusk came, and I had to go to the door and call to him.

“Dad,” I’d say, “it’s almost dark.”

He’d be on his knees again, bent over as if he were praying, and his voice, when he answered, sounded so far away. “Just a while longer,” he’d tell me. “I’m getting everything ship-shape.”

How could I not love him, when he was trying so hard to bring our lives back to normal?

Then one day our neighbor, Mr. Laskey, said to me, “Nathan, I see your old man crawling around on the grass. The last three days I’ve seen him. Did he lose something?”

Mr. Laskey, a retired chef, was the only one in the neighborhood who’d still speak to us. I told him about the mulch and how my father liked to keep it off the grass. “He’s particular,” I said. “He wants everything to be just right.”

“A soufflé I can understand,” Mr. Laskey said. “But mulch—how long is life?”

That evening, my mother called, and as soon as I heard her voice, as shy as a girl’s, I knew I’d do whatever she asked.

“Come out here and see the mountains,” she said. “You can’t imagine how beautiful the leaves are. Stunning. I’ve made a room for you. And there’s a good college. You could start next term…well, I’m not asking.” For a long time, I didn’t say anything. The phone lines were full of static, and I could hear the fuzzy echoes of other people’s conversations. “Nate, Nate, Nate,” my mother finally said with a sigh. “Did I do wrong? When I left your father?”

“Don’t ask me that,” I said.

“You can make a mistake and go back and change it,” she told me. “You don’t know that when you’re young.”

The pea vines were only a few inches tall—no more than half a foot—and staking them was a delicate job. First, my father had to push the bamboo sticks into the ground, close to the vines, but not so close that the sticks would damage the roots that were claiming a hold. Then he had to tie the vines to the stakes. His fat fingers fumbled with the slender shoots and the strips of nylon he’d cut from some of my mother’s old pantyhose. He had to lean each vine over so he could tie it to a stake without pulling the roots from the ground. He used nylon, he said, because it was flexible and wouldn’t choke the vines. It would give them the little bit of support they needed while still allowing them to grow.

“Do you want me to help you?” I said. “I’ve got time.”

“No, I don’t want you to help me.” He was crouched down, his head bowed, the straw of his gardening hat darkening from the drizzle. “I believe I’m quite capable of doing this job.”

But he was having a rough go of it. Each time he tried to tie the vine to the stake, the nylon got wrapped around his fingers or the vine slipped away from him. I crouched down beside him and smelled the wet dirt and heard the grunts of his breath.

“Just let me hold the vine,” I said.

I reached out and took the pea vine, and when my father tried to knock my hand away, the vine came out of the ground. I felt its roots, the thin white fingers, loosen their hold, and then there was the most incredible lightness at the end of my arm, and my father’s lips quivered with an uncertain smile. He looked like he was waiting for a punch line, not sure whether the joke was going to be funny.

“I’m sorry,” I told him.

“Sure,” he said, his grin vanishing. “Now you say it. Right when you’re on your way out the door.”

The trouble started that winter when I went out at night and hid myself close

to windows—crouched down behind shrubbery or heat pumps—so I could watch our neighbors in the warm light of their homes.

I never saw anything that they would have been ashamed for me to see. I can honestly say that: no quarrels, no lovemaking, no quirky habits. I told them that later, when I went from door to door, confessing what I’d done and explaining how I’d meant no harm or insult. I’d only wanted to be close to them. But, of course, by then, it didn’t matter what I said. I was criminal.

Mostly I saw them watching TV, eating sandwiches at the kitchen counter, rinsing dishes in the sink. Mrs. Poe liked to crochet. Miss Nance read the evening newspaper. Mr. Dean built model airplanes. Miss Stevens marked her students’ lessons and ornamented them with bright stickers or gold stars.

Mr. Laskey was my favorite. He cooked. I watched him in his kitchen, a long white apron tied around his neck. Even outside, I could smell oregano and tomato sauce, cinnamon and nutmeg. Or at least I convinced myself I could, eager as I was to breathe in the scents, take in the sights of settled, honest living.

In my own home, my parents operated a mail-order business called The Mutual UFO Network. My father transferred computer-generated images to videotape and created illusions of spaceships streaking across the night sky. He took out ads in magazines and sold his videotapes to customers around the world who wanted proof that what they’d suspected all along was indeed true: there were visitors from other planets, and they were watching us.

“We help people see what they want to see,” my father told me once. “What’s the harm in that?”

“It’s a hoax,” I told him.

“Hoax, schmoax,” he said. “It’s commerce.”

Then the unexpected happened. My mother began to wonder whether it might be true that we weren’t alone in the universe.

“All these people,” she said, waving a sheaf of order forms. “It’s something to think about.”

She’d read about a laboratory in Phoenix that, since the late seventies, had been testing photographs and videotapes to see if they were hoaxes, natural phenomena, or something unexplainable. Nearly three hundred fell into the last category, the mysterious and the possible, and suddenly that was enough for my mother. My father’s trickery, his blips of light across the screen, had already seduced her.

“Lunatics,” he said. “Good god, Lib.”

“I suppose that’s what you’d think about me if I ever came home and told you I’d seen a spaceship.”

“Let’s be reasonable,” my father told her.

But my mother just arched an eyebrow and stared at him, and I began to wonder what would happen if someone you thought you knew slipped away into another world. How far would love carry you if you wanted to follow? What if that person turned out to be you?

“I just don’t think we should rule anything out,” my mother said.

A few nights later, before I could see it coming, Miss Stevens turned off her kitchen light and saw my face at her window. What must I have looked like to her? It makes me ashamed to imagine. Then she screamed, and I ran, ran through the cold night, the air rushing up into my face, ran until Mr. Dean, dropping his garbage bag at the curb, stopped me, his arms wrapping around my chest. His hands smelled of airplane glue. “Nate,” he said with a laugh. “What in the world’s the deal?”

What I wanted to say was that I loved them, loved them all, the people I wished my family could be. But porch lights were coming on all along the street, and Miss Stevens was in her yard, shouting, “That’s him, that’s him, that’s him.” And all I could do was stand there and let Mr. Dean hold me.

How many times had I done this, my father wanted to know after Mr. Dean convinced Miss Stevens not to call the police and I was home, my secret revealed. How many houses?

“We’ll never be able to face these people again.” My father ran his hand through his hair, took a deep breath, and shook his head. “Jesus, Nate. What were you thinking?”

I was thinking how nice it had been every time I looked through a window and saw my neighbors’ ordinary lives, and how sad, too, to always be outside the light that enclosed them and kept them from seeing me. Night after night, I’d come home and found my father editing videotape, tracing his finger across a monitor’s screen. “There,” he’d say, tapping the screen with the point of his fingernail. “Now tell me, Nate. Doesn’t that look like the real McCoy?”

My mother, by this time, was already gone but hadn’t admitted it. She spent her evenings on our deck, a jacket hugged closed over her chest. She put her feet up on the railing, tipped back her head, and scanned the sky. One night, I joined her and watched the flashing red lights on an airplane. “If you ask me,” she said, “it’s selfish to think we might be the only life in the universe.” It was cold, and I could see her breath. “It’s such a big place, Nate. How do we know?”

“Do you really believe it?” I said. “All this stuff about UFOs?”

“I don’t believe it the way I believe in love,” she said. “But it’s an interesting prospect.”

She’d always been a woman on the lookout for the rare and unusual. That’s how she found my father, who at the time, 1976, had been selling Bicentennial rocks on college campuses. “He had this suitcase,” my mother told me. “And it was full of rocks, just plain rocks. Nothing painted on them. No American flag or eagle, not even the date. ‘They’re just rocks,’ I said to him. ‘Why would anyone buy a rock?’ ‘Not rocks,’ he said. ‘Bicentennial rocks. Years from now, when you look at this rock, you’ll think, 1976, and then you’ll remember everything.’ He had this way about him, even then. Your father has always been very sincere.”

He’d always been a shyster, and like all good shysters, he believed every lie he told. “We’re going to figure this out,” he finally said the night Mr. Dean brought me home. “Don’t worry, Nate. We’re going to be all right.”

But it was too late. My nightly peeks into my neighbors’ windows had given my mother a glimpse of escape. “Tell me,” she said later, when she came into my room and sat on my bed. “Tell me what you saw.”

I’d decided to drive myself to the airport and leave my car in long-term parking because I couldn’t face the prospect of sitting on a plane knowing my father was standing behind the wide spread of glass in the terminal watching the takeoff, watching until the plane had climbed above the cloud cover and disappeared. “I stood right there,” he’d told me after I flew to California with my high school band to march in the Rose Parade. “I kept watching until I couldn’t see you anymore.”

This time, before I left, he hugged me in the garden. He threw his arms around me and pressed me to him. My forehead hit the brim of his hat and it tumbled to the ground.

“It’s not your fault,” he said. “What’s happening to your mother and me. We’re just putting a little air between us. You know. Taking a rest. I fully expect she’ll come back soon.”

I drew away from him and saw his face, wet now from the rain. “She’s all set up in Virginia,” I said. “She sells timeshares at a resort village.”

“You tell her I’ve changed,” he said, and his voice was a whisper. “You tell her, Nate, and she’ll come back. It was all that UFO crap that caused the problem, but, hey, I was just trying to make a buck on the side. I didn’t give anyone anything they didn’t deserve.”

At the airport, a man was selling books. He was cruising through my boarding area, dragging a canvas duffle bag behind him. The bag kept bumping into people’s carry-ons, kept whacking their shins. “Sorry,” the man kept saying. He was a young British man with a winning smile. “Terribly sorry.” The books, he told people, were collections of stories, each volume focused on a different subject. He had travel stories, wedding stories, brother stories, war stories.

“Each one of them true,” he said. “Not a word made up. This is the real stuff. People just like you.”

The young man was wearing an emerald-green polo shirt and a pair of khaki slacks that still had creases in them fro

m being folded in the store. The tassels on his loafers—those, too, shiny and new—slapped against the tops of his feet as he made his way up and down the aisles of plastic chairs.

“What about you, mate?” he said to me. He leaned over and put his face close to mine. I smelled the strong citrus scent of his cologne. “Something to read on the plane?” I hesitated just long enough to give him the chance to keep talking. “What’s your cup of tea? Adventure? Romance?” He jostled my arm with his elbow and winked. “Erotica?”

Sitting across from me was a man who kept chewing his fingernails. He bit them off and spit them onto the floor. He was a skinny man with a gold tooth, and every time he gnawed at a fingernail, that tooth—an incisor—caught the light and twinkled. The woman who was with him, a woman with no hair—just a shadow of fuzz—and a very soft voice, said, “Would you calm down? Would you just calm down? Planes go up and then they land. Hundreds of them every day. It’s perfectly safe.”

The nail-biter, this guy with the gold tooth and a few scraggly whiskers on his chin, put his hand on the woman’s head. He palmed it like it was a melon and squeezed. The woman tried to pull away. She tried to stand up, but the nail-biter kept pressing down with his hand, a hand that looked like it wasn’t even his. It was so broad and the fingers were so long. It looked like something made out of plastic, a fake hand, but I knew it was, as my father would have said, “the real McCoy,” by the way the woman grimaced and bit down on her lower lip. “You are,” she said in that soft voice of hers. “You are.” I knew, from the way she said it, that this was a regular occurrence, something she had to endure with the nail-biter. She had such a lovely face, her skin smooth and glowing, that it was easy to forget she had no hair. It was something about her eyes, I decided. They were eager eyes, wide open and trusting, the kind of eyes my father must have imagined on every sucker in the world. She looked like she could get on a plane, without a thought of crashing, go anywhere in the world, and feel at home. Whoever she was, and whatever her story was with the nail-biter, I felt certain she didn’t deserve the way he was treating her. It made me think of all the people who’d sent in their money for my father’s fake videos.

Late One Night

Late One Night River of Heaven

River of Heaven The Bright Forever

The Bright Forever The Mutual UFO Network

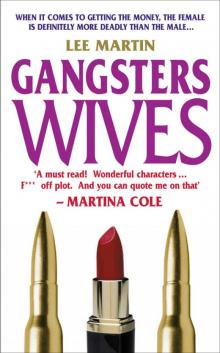

The Mutual UFO Network Gangsters Wives

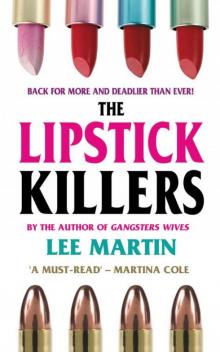

Gangsters Wives The Lipstick Killers

The Lipstick Killers