- Home

- Lee Martin

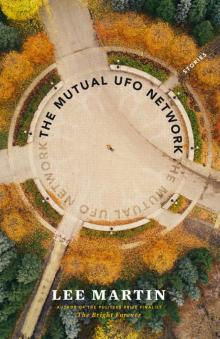

The Mutual UFO Network Page 24

The Mutual UFO Network Read online

Page 24

And I’ll have to hope you weren’t watching that night when I pulled in behind the Mister Peanut, and I cut the engine, and I said to Doogie, “You’ve been cooking meth here, haven’t you?”

“What’s this?” he said. “The third degree?”

“No,” I said, “it’s the third sign.” The first, like I’ve said, was that tattoo; the second was the linden tree. “The third sign of what?”

“Of peace,” I said, and it surprised me to say it. “Of letting go.”

I made him help me. I told him it was the only way I’d let him have that money. I had the gasoline in a can in the bed of my truck. Doogie knew how to get into the Mister Peanut. It didn’t take much. A can of gas, a match, and before the flames could lick through the roof, we were gone.

I drove Doogie out to his place in Goosenibble. The air stunk of the poultry house. I sat there waiting to catch the first whiff of smoke, to hear the alarm at the firehouse.

“You’re not giving me that money, are you?” Doogie finally said.

“I can be a cruel sonofabitch,” I told him.

“So can we all, Baby James.”

“You tell the cops whatever you’re a mind to.”

I reached across him and opened the truck door; I sent him away to make up his mind.

That was the last time I ever saw him.

I went home to your mama. She was still awake, sitting on the couch, her knees up to her chin, looking for all the world like the girl I first fell in love with.

“It’s late,” she said. “We’ll be worn out come time for work.” I sat down on the couch beside her. “The Mister Peanut’s on fire,” I said.

She was hugging a pillow, a look on her face like she was scared to death. “Trees falling,” she said. “Places burning. What’s next?”

She thought we were at the end of something. “Maybe someone’s not living right,” she said.

But who’s to say? There was all that money, and I could be a fool cranked up on hope, pretending, even after I’d turned all that cash over to St. Jude’s, that it was enough. But like Doogie said: it just goes, and there’s never enough of it to stop all the heartache in the world and never enough of it to stop us from trying.

I reached over and took your mama’s hand. We sat there, holding on, not saying a word, until, finally, the sun came in through the window and got into our eyes, and your mama said, “You ready?” And, April, I told her I was.

DUMMIES, SHAKERS, BARKERS, WANDERERS

THAT WINTER, MONA WAS IN THE HABIT OF RISING BEFORE DAWN. While Wright still slept, she went out to the barn to check on the Clydesdale mare. She liked stepping out into the cold, looked forward to those first breaths of icy air that stung her eyes and nose and stuck in her throat. She liked the sound of her boots squeaking over the packed snow, the glow of the pole light in the barnyard, the vapor of her breath hanging in the air. Most of all, she loved to hear the Clydes nickering in their stalls and to feel the solid bulk of them when she finally rubbed her hand over their withers and haunches and flanks.

Later, in the warmth of the kitchen, where by this time Wright would be drinking coffee, she would wait until he had heard the farm market reports on WVLN, and then, passing behind his chair, she would let her hand trail along his back, petting him, and she would tell him that the mare was fine.

“She’s a tough old gal,” he might say. “No quit in her.” Then he would gulp down the last of his coffee and hurry out to his truck.

Just before Thanksgiving, he had been hauling the mare, Lucy, back from a breeder in Texas when the hitch had come loose and the trailer had toppled and Lucy had come out the back and gone sliding on her side down a snow-covered I-57. It had been a miracle, Wright told Mona, that no one had hit her. “Everyone was driving careful,” he said. “Hell, I was barely doing forty, taking it extra slow, and then a thing like that had to happen. I could shoot myself.”

Their son, Gary, was still living with them then, and there was a month between Thanksgiving and Christmas when he was clean, the methamphetamine a nightmare fading. He talked about enrolling in some classes at the junior college, maybe even going to the U of I and getting a degree in landscape architecture, and Mona, caught up in his optimism, said yes, wouldn’t that be fine. She refused to consider how precarious this time of grace might be—indeed by New Year’s Gary would be using again. She preferred to watch him and Wright grooming the Clydes, the two of them paying particular attention to Lucy. Gary used the curry comb. He was tall and slender, and his long arms moved over Lucy with graceful sweeps and arcs that reminded Mona of a willow’s branches lifting and falling with the wind. Lucy swung her face around and nuzzled him, and it was as if Mona was seeing this for the first time. After all the years of raising Clydes, she thrilled again to how gentle they could be. Wright used the hoof pick. He was patient and fastidious. He sweet-talked Lucy as he cupped an ankle in his hand, and she stood there, a foot lifted like a lady about to test the temperature of her bath. “Lucy girl.” He flirted with her. “Who’s my girly-girl?” Mona watched Gary and Wright moving among the Clydes, pampering them, and she let the sweetness fill her.

Now when Wright left each morning and she was alone, she dreaded the long day ahead of her, the Clydes the only bright spot. At least she had them to care for. Where Wright went those winter mornings, he never said. Later, she heard from friends that they had seen him in town at Turnipseed’s Coffee Shop, or at the grain elevator, or at the city park slouched down in his truck, the engine running. It was clear to her that he really had nowhere to go those mornings and only left home so he would be away from her and their house, which was now a place filled with regret.

“Stop blaming yourself,” she told him once.

“Can’t,” he said. “I’m the one who caused it.”

“It’s no one’s fault.” She repeated a line she could remember her mother saying. “Is just is.”

But she didn’t believe it, not in her heart of hearts. There she couldn’t stop wishing that Wright had the courage to put the blame where it truly belonged—on her.

She had been the one, after all, who had said to Gary, that day after New Year’s, “Either you get help or we put you out.”

They had all been in the kitchen on an afternoon when a cold rain was falling. Gary was at the sink, drinking a glass of water. He was always drinking water when he was using, gallons and gallons it seemed. The meth dried out his mouth, and he was always thirsty. He tipped back his head and his Adam’s apple slid up and down his throat. When the glass was empty, he wiped his lips with the back of his hand. He shook water drops from the glass and held it up to the light, turning it around with his long, narrow fingers.

“I bet I could eat this glass,” he finally said. He put one side of the rim into his mouth, and Mona heard his teeth click against it. When he was on a run, cranked on meth, he got the idea that he was invincible. He had been in and out of the hospital after trying all sorts of foolish stunts: he had gashed his forehead in a car wreck, broken his leg while trying to climb the water tower, burned his hand because he had been convinced he could reach into fire, shot a nail from a pneumatic gun into his scalp because he wanted to let some air in and relieve the pressure in his brain. He took the glass away from his mouth and winked at Mona. “Tell you what, Moma.” (He had always called her Moma, his mouth rounding with the long o sound, a pet name she was glad he had carried over from childhood.) “If I eat this glass—eat the whole damn thing—you and me, we’ll call things square. I’ll kick the meth. Go to that clinic in Champaign like you want. Otherwise, I’ll walk out that door and go away so you won’t ever have to be ashamed of me again.”

“We’re not ashamed of you,” she said. “Tell him, Wright.”

But Wright wouldn’t answer. He just kept staring at Gary, who was still holding the glass.

“Well, Dad?” Again, Gary put his mouth around the rim of the glass.

That’s when Wright swung his arm, the back of his h

and knocking the glass away from Gary. It hit the wall and shattered. A trickle of blood leaked from Gary’s lip. And Wright, something unleashed in him, hit Gary in the face with his fist. He caught him on the jaw, and Gary’s head snapped back. He covered his face with his arms, but still Wright kept punching, his fists beating against Gary’s wrists. Mona tried to pull Wright away, but he shook her off. He was grunting with the punches. Gary had started to whimper and squeal, the way he had as a boy when he had bad dreams. Mona was tugging at Wright’s sleeve, his collar, his neck, anything she could get hold of. Gary was sinking down to the floor, his arms still crossed over his face. Wright leaned over, still trying to reach him with his punches. Mona had him by the shoulders, and they were off balance. They toppled over, and then there they were, the three of them in a heap. Wright was breathing hard. Mona’s hair had fallen over her face. They untangled legs and arms. Gary uncovered his face and Mona saw the bruise on his jaw where Wright’s first punch had landed. She reached out her hand to touch it, but Gary turned away.

Outside, the rain had turned to sleet and was peppering the kitchen windows.

“Look at us,” Mona said. “Just look at us.”

Gary grabbed onto the kitchen counter and pulled himself to his feet. Wright slumped over and covered his face with his hands. Gary grabbed his jacket from the peg by the door and went out into the sleet. That was the last time they saw him. He got into his Firebird and drove away.

They had no idea where he was, whether he was alive or dead, whether they would ever see him again. All Mona could do to get through her guilt for not being more forgiving, more tolerant, was to focus on the solid, knowable things around her: the snow and ice and cold, the Clydes, particularly the mare, Lucy, who was now so close to foaling.

One morning, Mona stepped outside just as the sky was beginning to brighten in the east. The bare limbs of the beech and hickory and sweetgum in the woodlot beyond the pasture’s end were just starting to emerge from the darkness, and in the dim light they seemed to her a jumble of arms, frantically reaching.

More snow had fallen sometime in the night, and the wind had drifted the barn lot. She had to shovel snow away from the door before she could swing it open, and still the bottom scraped. She was thankful when she finally slipped into the feedway and breathed in its familiar aromas: straw and hay, oats and tack, manure and horse.

She went to the first stall and saw Lucy down on her side. The birth sac, its white balloon, sagged from between her hind legs, and Mona could see the foal’s front feet inside the sac and then its nose. Her first instinct was to run back to the house and wake Wright—she had never tended to a foaling by herself—but then she saw that the foal, its head and chest visible now, had stopped moving. She knew there was no time for her to run for Wright; she would have to tear the birth sac before the foal suffocated.

When she did, she could see that the foal wasn’t breathing. She tried to stay calm, to think what Wright would do. Then it came to her, the simplest thing: she took a piece of straw and tickled the foal’s nostrils until they flared. She felt warm breath on her hand.

The foal surged and its hindquarters emerged. Mona held the rope of the umbilical cord and felt the pulsing of blood. Each pulsation stretched the elastic cord and felt as large as pullet eggs in her hand.

Confident that everything was as it should be, she backed out of the stall, knowing she had to get out of the way so Lucy could finally stand and break the cord and find her foal.

Mona felt something tearing at her heart, and she knew, then, that what she feared most, now that Gary had gone, was that she and Wright would become strangers, each of them wandering inside their own circle of guilt, unable to reach through to the other. She imagined bringing him out to the barn and showing him the foal, bright-eyed, wobbly-legged, full of promise and hope. It would be a single good thing, this gift, and maybe it would start a healing.

When Lucy finally broke the cord, Mona went back into the stall and dipped the stump in an iodine solution so bacteria wouldn’t pass through it and leave the foal with navel ill or joint ill. “Good girl,” she said to Lucy, who was nuzzling the foal, licking it clean. “Good Lucy girl.”

Suddenly the foal’s head jerked, and then its legs, and it began to bark again and again, the yip of a small dog—a terrier or a Pekingese, and Mona, watching, felt a chill pass through her. She knew she would have to wake Wright and tell him the foal had come, and instead of a gift it would be a sad, troublesome thing, because something neither of them could have seen coming had gone wrong.

“It’s a dummy foal,” the vet said. Wright and Mona were kneeling in the straw, trying to hold the shaking foal steady while the vet sedated it with an injection of Diazepam. “Dummies, shakers, barkers, wanderers,” he said. “They’re all terms for what I’m afraid you’ve got here, folks—NMS, neonatal maladjustment syndrome.”

It was, he explained, a problem that came along from time to time. No one could predict when or even fully understand why. Some thought the condition resulted from sustained cerebral compression in utero or during delivery. Others blamed it on oxygen deprivation either during the latter part of pregnancy or during foaling.

“Darnedest thing,” the vet said. He wore half-glasses on a cord around his neck, and they sat on the end of his nose as he finished the injection. “A real mystery. We’ll do what we can and keep our fingers crossed. I’m sorry it’s happened to you.” He shook his head. “Here it is, one more thing for you to deal with.”

“One more?” Wright said, and Mona heard the anger in his voice.

“I only meant…”

“I know what you meant.”

The vet busied himself with inserting a feeding tube into the foal’s stomach. For a good while, neither he nor Wright spoke. Mona kept her head bowed. How easily the vet had acknowledged their trouble, had made it known that their misery with Gary was common talk. She laid her hand flat against the foal’s neck and felt the nerves twitching. Suddenly she was overwhelmed with a sense of how they were all connected, all the—what was it the vet had said? Dummies, shakers, barkers, wanderers. Maybe the best God could do was to align the universe so that all those who suffered could find one another.

“It’s just rotten luck,” she said, unable to bear the silence any longer. “Or maybe not.” She stroked the foal’s neck. “Maybe we’re lucky.”

She looked over at Wright and saw him staring at her with heat in his eyes. “How the hell to do you figure that?” he asked.

“Someone’s got to be here to know this.” The foal’s eyes weren’t moving. They set in a fixed stare as if they weren’t eyes at all, but marbles or ball bearings. The barking had fallen back to an occasional whimper. “You know what I think? God doesn’t…”

“Mona.” The vet interrupted her. “It’s all right to be angry. No one would blame you a bit.”

She knew he thought that she had meant to say, “God doesn’t give us more than we can bear,” but what she had really been thinking was how the hurts of people were nothing without someone else to witness them. They were just howls in the dark. “God can’t take in people’s pains the way we do,” she had meant to say. “That’s what he expects from us: to bear witness, to know how close any of us are to anguish. That’s our job.”

“Maybe I’m angry,” she told the vet. “Sure. Maybe a little. But I don’t have time to dwell on that. Now, what do we have to do to save this foal?”

It would require keeping the foal warm and hydrated, the vet said. He would set up an IV to drip sodium bicarbonate into the left jugular vein, and antibiotics as needed. The feeding tube would handle the necessary nutrition. The most important thing now was to get some colostrum into the foal. Mona knew that this first milk from the mare was high in protein and natural antibodies that the foal’s immune system would need. Since the foal couldn’t suck from the mare, the vet would have to give them some frozen colostrum. “Thaw it at room temperature,” he said. “If you microwave or heat

it, you’ll destroy the antibodies.” He told them to turn Lucy out to the pasture so she wouldn’t disturb the foal and set it to shaking and barking. “We’ll keep it sedated and well-fed, and then hope for the best.”

“What are our chances?” Wright asked.

“Fifty-fifty,” said the vet.

Wright shook his head. “I’d like it if they were better.”

In the kitchen, while they waited for the colostrum to thaw, Wright shelled peanuts from a bag he had brought home just before Christmas from the Trading Post Antiques store in Olney.

He had bought sacks of chocolate drops and peanuts, horehound drops and peppermint sticks, rock candy and divinity, the way he had when Gary was a boy—all this because Gary was clean and they were celebrating. Now the holidays were over and Gary was gone and there was all this loot. Wright pressed the peanuts between his thumb and forefinger and emptied the nuts out onto his palm.

“It’s a hard thing,” he said. “That foal. The vet’s right. One more hard thing.”

For a moment, Mona felt closer to Wright than she had in a good long while. His voice was toil-worn as if his words were stones he had to shove against to move, and she ached to see the slump in his shoulders. She knew they were nowhere near the end of their misery. She went to him and took his hands in hers.

She had no words for what she wanted him to know, only the heat of her skin, the squeeze of her hands. She let herself lean forward, bowed her head until it rested against his chest, and for a while, they were all body, neither of them speaking, relying instead on the silence, on the rise and fall of their breathing.

Then Mona heard the door open. She felt the icy air across her back and legs. When she turned, she saw Gary standing in the doorway, waiting, she imagined, for someone to tell him it was all right to come in. He was wearing an oversized flannel shirt, the tails hanging down to his knees. His eyelids were fluttering, and he was moving his head about, his eyes looking right, left, up, down like a bird on guard, ready to lift from the ground and fly at the first sign of danger. Mona knew right away that he was using.

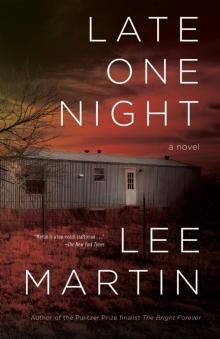

Late One Night

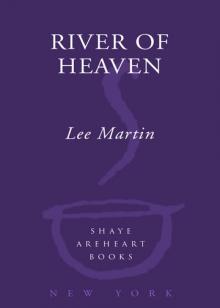

Late One Night River of Heaven

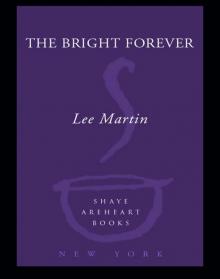

River of Heaven The Bright Forever

The Bright Forever The Mutual UFO Network

The Mutual UFO Network Gangsters Wives

Gangsters Wives The Lipstick Killers

The Lipstick Killers